Kunal Purohit is an award-winning independent journalist, documentary filmmaker, and author who has written extensively on development, politics, inequality, and the rise of Hindu nationalism.

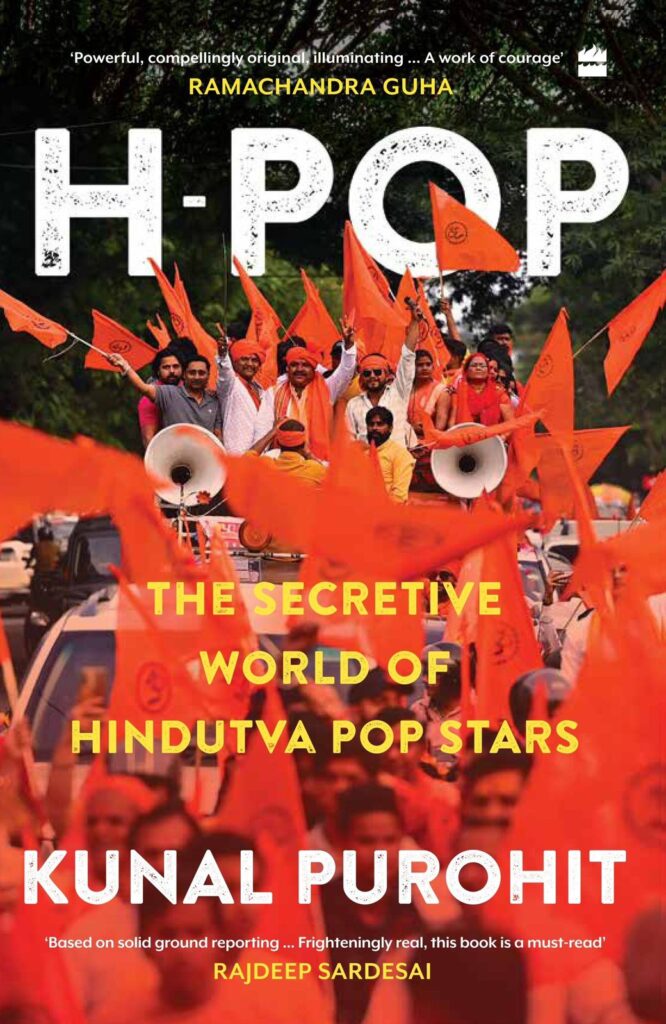

Kunal’s recent book, “H-Pop: The Secretive World of Hindutva Pop Stars” delves into the infiltration of Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) ideology into popular culture and its alarming consequences, including the normalization of Islamophobia and violence.

In this interview, Kunal sheds light on the insidious world of the Hindutva pop industry, the role of social media platforms in financing and amplifying hate music and its growing reach beyond India’s borders.

The conversation, edited for length and clarity, is as below.

N Fathima (NF): How do you think Hindutva pop is ushering in a dark era of anti-minority hate in India?

Kunal Purohit (KP): We have seen this spectre of hate speech towards minorities slowly build up in the last few years. We’ve seen hate speeches being delivered within the parliament and outside at political events. The popular traction is what makes this phenomenon so peculiar. This rhetoric targeting minorities has always stayed within political confines. When you’re at a hate speech event or at a rally where people are delivering hate speeches, it’s an inherently political space. The act of making that speech is also then inherently political.

What we’re now seeing is a departure from those patterns because hate speech is no longer confined to those political spaces anymore. Hate speech and hateful rhetoric are now increasingly entering the realm of popular culture, like music, poetry, and books. This normalizes hate because entertainment is now interspersed with very rabid hateful speech. You may think you’re just consuming a song or a poem or reading a book, but you’re actually consuming a very hardline Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) agenda. This shift in packaging has made it incredibly easy for anyone to unwittingly consume hateful content. Whether browsing YouTube, driving, or cooking, individuals can be subliminally exposed to the Hindutva agenda. This represents a radical departure from previous trends.

By embedding hateful rhetoric into popular culture, its normalization receives a significant boost. The message no longer appears overtly political; instead, it’s disguised within entertainment content, thereby normalizing and popularizing the ideology. Now, you have widely followed artists, poets, and authors who echo the sentiments expressed at hate speech rallies, albeit in a different guise. This normalization has broken the boundaries of where this hateful rhetoric exists: once the floodgates are broken, the hate flows everywhere.

NF: How have Hindutva influencers managed to gain traction and influence without drawing the attention of media and civil society to their hateful and violent messaging?

KP: I’ve been closely monitoring the trajectory of popular culture content for the past five years. In 2019, when I first encountered this phenomenon, most of such content was primarily found in smaller towns and rural or semi-rural areas. However, we’re witnessing a notable shift: this popular culture has made its way into larger cities. As it traversed the divide between semi-rural and urban areas, its appeal broadened. Yet, this growth occurred largely unnoticed in areas where neither the media, journalists, nor broader civil society were actively tracking its development.

One significant contributing factor to this oversight is the absence of a robust media infrastructure that invests in on-the-ground reporting in remote regions. We’ve also seen the death of local reporting in many corners of the country.

There’s a prevalent misconception that the entire country uniformly consumes popular culture. We assume everyone watches the same Netflix shows, films, or movies. However, when Hindutva popular culture emerged in these spaces, it initially appealed to specific segments of the population, who either dismissed it or embraced it without much scrutiny. Neither group raised concerns or questioned the content being created. The media’s failure to fulfill its role exacerbated this issue.

Even other pillars of our democracy, such as the judiciary and police administration, viewed this phenomenon primarily as a law-and-order issue rather than a broader sociological challenge. While some police officials were aware of what was happening, they lacked the understanding to address it effectively. Their responses typically focused on regulating events where such content was played rather than investigating the creators or assessing the wider ecosystem at play. You’d be surprised at the number of people who walk up to me each time I talk about my book and tell me they’ve never heard of anything like this. It indicates a significant disconnect between different segments of the population in terms of their media consumption and worldview formation.

NF: What role are social media platforms playing in amplifying the reach of Hindutva pop artists?

KP: Platforms like YouTube are not merely passive hosts; they actively abet and fund much of this content. For many pop stars, revenue from their YouTube channels constitutes a significant portion of their income. Essentially, YouTube incentivizes them to produce higher-quality songs and videos, encouraging them to return with fresh content for the platform.

YouTube has played an active role in establishing a stable and lucrative revenue stream for these creators, underscoring the need for a more critical evaluation of its role in perpetuating misinformation. There is mounting evidence suggesting that YouTube isn’t merely turning a blind eye but actively funding the creation of such content.

Moreover, it’s essential to recognize that this phenomenon extends beyond YouTube alone. Almost all songs by Hindutva pop stars are accessible across various streaming platforms, including Spotify, YouTube Music, and Apple Music. These platforms also host hate-filled music, contributing to the funding of such content through royalties and revenue per listen. Numerous digital outlets have become complicit in financing and promoting these creators, ensuring their continued success and amplifying their reach and influence.

NF: Do you think social media contributes to amplifying this content for a specific audience?

KP: One hundred percent. This isn’t something new. Repeatedly, we’ve observed how social media platforms strive to cocoon users within comfortable echo chambers. If you express distaste for certain political content, these platforms ensure it never appears on your feed. Likewise, if someone likes a song by Kavi Singh (Hindutva pop singer) on the topic of Muslims and “love jihad” (anti-Muslim conspiracy theory), the algorithm will promptly suggest a similar song by Sandeep Acharya (Hindutva pop singer). These platforms meticulously tailor suggestions to align with your interests, fostering an environment where users remain unaware of each other’s consumed content.

NF: How is Hindutva pop financed?

KP: We’re noticing that they’re innovative in how they generate resources. For example, someone like Sandeep Deo (publisher of Hindutva books) consistently appeals to his followers for funding. If you’ve seen any of his videos, you will notice he repeatedly makes these appeals, urging his audience to support him so he can continue his work. There’s a direct connection between creators like him and their audience. Additionally, Sandeep Deo’s creation of an e-commerce website is a move towards establishing sustainable revenue streams while promoting his agenda. He calls Amazon and other e-commerce platforms anti-Hindu and seeks support for his own e-commerce platform, which he calls Hindu-centric. He not only sells books aligned with his agenda but also Hindu ritual items, essentially nudging his audience towards a devout Hindu identity. This alignment with his brand contributes to his success in garnering donations and book sales from his platform exclusively. Selling 25,000 copies a year solely through his website is no small achievement.

Similarly, artists like Kavi Singh and Kamal Agney (popular Hindutva poet) are exploring ways to monetize their work. Kamal engages in various content creation endeavors, like writing poetry and promoting it on social media. At the same time, Kavi also focuses on building his social media presence and performing at paid events. Social media platforms, however, play a crucial role in expanding their audience reach. A larger audience translates to more performance opportunities and higher fees for them. Sandeep Deo, for instance, utilizes platforms like YouTube and Facebook to direct traffic to his e-commerce site. Essentially, social media platforms serve as facilitators, connecting creators with broader audiences and enriching them financially in various ways.

NF: What are the connections between the Sangh Parivar (family of Hindu far-right groups) and these influencers?

KP: Well, there are undoubtedly connections linking Hindutva pop culture with various Hindu right-wing organizations like the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS), Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), Bajrang Dal, and numerous smaller outfits. However, it would be a mistake to view all these pop stars and creators as mere products of sponsorship, either financial or otherwise. They aren’t individuals funded by these organizations to continually promote their agenda. What these Hindu right-wing outfits do for these creators is occasionally provide them with larger platforms for their work to reach a broader audience. For instance, they might invite artists like Kamal Agne or Kavi Singh to perform at their events, paying them for their appearances. While these opportunities may enhance the creators’ visibility, it’s insufficient to claim they’re all funded by these outfits.

More importantly, these creators often gain access within the Hindu right-wing ecosystem, leading to more gigs or more lucrative assignments. Many of them find employment with organizations affiliated with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) or agencies working closely with them. This could involve tasks such as writing content for supportive Facebook pages or other paid assignments facilitated by sympathizers of the Sangh. These connections are intricate and multifaceted, far from the simplistic assumption that everything in the Hindu right-wing ecosystem is funded by the BJP or RSS.

It’s crucial to understand that this relationship is reciprocal rather than one-sided. When these organizations recognize a popular figure promoting Hindutva with significant traction, they may seek to co-opt them for their cause. However, this typically occurs once the individual has already achieved a certain level of popularity or produced viral content. For example, Kanhaiya Mittal gained attention when his song “Jo Ram ko laaye hain, hum unko laayenge, UP mein firse hum Bhagwa lehraenge (We will bring those who have brought Ram, we will bring them, and once again we will raise the saffron flag in Uttar Pradesh)” went viral on the eve of the Uttar Pradesh elections. Only then did the BJP officially engage him as a campaigner.

So, these organizations do not actively scout for talent but rather observe closely and enter into reciprocal relationships when they deem it advantageous. It’s a carefully calibrated process, not a simplistic sponsorship model.

NF: How are Hindutva influencers reaching audiences outside of India? Are they?

KP: Absolutely, there are numerous instances illustrating this phenomenon. Take, for example, the car rallies organized in various parts of the world in support of the BJP and the Hindutva. If you listen closely to the music played at these rallies, you’ll often hear Hindutva pop songs, some of which I’ve mentioned in the book. This trend is evident.

Moreover, Sandeep Dev’s published books garner orders from individuals worldwide. He ships these books to people in different countries, including diaspora audiences who are sympathetic to the Hindutva cause. This popularity extends beyond India, with diaspora audiences not only endorsing but also financially supporting various elements of Hindutva-influenced popular culture. They may host events like Kavi Samelans abroad, purchase books, or even provide direct financial support to artists. This transnational solidarity and support for these artists highlight that the reach and impact of Hindutva-influenced pop culture extend far beyond India. It’s a global phenomenon.

NF: What do you think the future of Hindutva Pop is? Do you foresee the cultural and social capital of Hindutva influencers growing?

KP: What we’re witnessing is that the Hindu right-wing ecosystem has discovered an incredibly convenient and potent method of mobilizing support, popularizing its ideology, and radicalizing individuals. This form of campaigning for the Hindutva cause doesn’t rely on hate speeches, expensive events, riots, or violence. Instead, it operates seamlessly without any on-the-ground mobilization. The method involves disseminating political messaging through easily accessible channels. Individuals can simply click a few times to listen to a song or poem that conveys the same message as a hate speech delivered at a rally. What’s particularly concerning is that this political messaging infiltrates personal spaces. Whether you’re in your car, at home, or on public transport, you’re exposed to this content, which normalizes and entertains while spreading its ideology.

This weaponization of popular culture is insidious and dangerous. It doesn’t require individuals to attend rallies or engage directly with political figures. Instead, it subtly indoctrinates and radicalizes people while they enjoy music or poetry. This makes it a potent tool for spreading the Hindutva ideology. I express concern in the book that we’ll continue to witness an escalation of this phenomenon, with increasingly sophisticated forms of weaponizing popular culture. Already, we’re seeing this trend extend to cinema, further amplifying the dissemination of the Hindutva ideology through more polished and widespread means. I fear that this trend will only intensify in the future.

(N. Fathima is an Associate Research Fellow at the Center for the Study of Organized Hate.)